“Imagine you have a friend name Rob,” says our instructor at the University of North Florida Writer’s Conference. “If you want to ask your friend a question, you might begin by saying, ‘So, Rob…’ and that is how to pronounce my first name.”

Sohrab Homi Fracis (“Fray-sis”) is the first Asian writer to win the prestigious Iowa Short Fiction Award. He received it in 2001 for his collection of short stories, Ticket to Minto: Stories of India and America. He resisted advice from publishers to combine the thematically related stories into a single novel, which they thought would be easier to sell. Fracis believed passionately that the stories stood strong and worked best as they were.

“And I was proven correct,” he says.

India Magazine calls the book, “Stunning in its breadth and scope of language and description … a fresh voice in South Asian fiction,” and adds, “One can grow tired of Rushdie wannabes, mother-in-law stereotypes, and village parodies. Fracis’s writing is brutally honest, exposing sinew and nerves and getting at the heart of the matter.”

Lenore Hart, author of Waterwoman, says Ticket To Minto “evokes the snaky path to adulthood, exposing all those hitchhiking demons at the intersections. From Caulfieldesque schooldays in Bombay, to assimilation amid the seductive consumerism and residual racism of American culture, a powerful, serio-comic look at two worlds, inside and out.”

Sohrab is currently writing a novel called Go Home, which he says he has been pitching to publishers as “Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake meets Kerouac’s On the Road”. An excerpt from the novel, published in Slice Magazine, was nominated for a 2010 Pushcart Prize. Another excerpt appeared in South Asian Review.

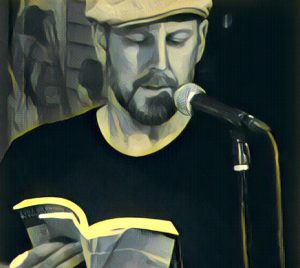

Sohrab Homi Fracis was born in Mumbai (then called Bombay), India. He first studied engineering, then computer programming, then became a systems analyst, which brought him to the United States. He went back to school for an M.A. in English and creative writing at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville. He taught literature and creative writing at this college from 1993 to 2003, and is now retired from teaching except for his participation as an Instructor for the annual University of North Florida Writers Conference. A few months ago, I went to an open-mic prose and poetry reading at one of Jacksonville’s most popular independent bookstores, Chamblin’s Uptown. At that time, I knew nothing of Sohrab and his awards, but his reading of a selection from Ticket To Minto motivated me to buy the book. I enjoyed every story, and a couple of months later attended the UNF Writer’s Conference. Sohrab’s Critique Workshop was, for me, the educational highlight of the experienence. The man is serious about the craft of writing, somehow amiable and intense at the same time, and reads aloud with an agreeably expressive resonance. One student said, “He reads like Paul McCartney sings.”

I didn’t want to wait another year to ask him questions, so I arranged to interview Sohrab for Literary Kicks.

Bill: The ending of your book’s title story, “Ticket to Minto”, left me unsure as to how I felt about the aggressive actions of the Mintoan students. The uncertainty was a not altogether unpleasant, but rather felt akin to the enthusiasm I felt as a teenager for movie anti-heroes like motorcycle gangs and western gunfighters. Did you intend to elicit this feeling?

Sohrab: I didn’t mean to portray the Mintoans as anti-heroes (though I’m fine with your reading/experiencing/enjoying them that way), so much as almost ridiculously complex men: excessively polite and generous under certain circumstances, but crude and murderously violent under others. As a result, the story’s narrator is ambivalent about them, and in conveying the story through his perceptions, I do intentionally impart that ambivalence to the reader and a strong sense of their complexity. At roughly midpoint of the story, the reminiscing narrator says of the Mintoans, “Something in me has always said that if I could understand them, I could understand myself; if I could understand them, I could understand our country in all its callow bombast and hoary wisdom; if I could understand them, I could understand the world.” He’s getting at that wide-ranging complexity in the central clause, and extending it to all of us. Underneath our socially constructed veneers, we’re genetically and biochemically complex creatures, capable of a wide range of characteristics in response to the relevant stimuli (short-term and long-term). I used to say to my lit students at University of North Florida: “Show me someone you think is ‘a simple man,’ and I’ll show you that still waters run deep. Show me someone who thinks of himself as a simple man, and I’ll show you someone who’s deluding himself.” That goes for women too, of course; I was just bouncing off the commonly used phrase.

Bill: What are some projects you worked on as a computer programmer?

Sohrab: Let’s see: I first programmed in Bombay, India, for an overseas Swiss project, before Bombay was renamed Mumbai and outsourcing was even a word. Next, I was contracted to HON, a Fortune 100 office-furniture manufacturer in Muscatine, Iowa, which would later become the setting for my story, “The Mark Twain Overlook.” The name of that scenic point overlooking the Mississippi stuck in my head long before I became a writer. Then I was contracted to Ford, in Detroit, coding for the Plymouth Assembly Plant. That later gave me the settings for a couple of stories in Detroit. And finally, I developed systems here in Jacksonville, Florida, including an online system for the School Board. Soon thereafter, like the aspiring writer in “The Mark Twain Overlook,” I “left the writing of code to go write my own stories.”

Bill: Does India have any fiction genres not found in America, or conversely, are there genres in America that you rarely or never find in India?

Sohrab: Well, there are the ancient Indian epics, in particular the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, but others as well, from an oral storytelling tradition, originally, and transcribed first in Sanskrit, I think. That’s a fiction genre not to be found here (and one that can no longer be created), unless there are American Indian epics (not just the briefer, separate legends) that I’m not aware of. Even if there are, the difference would be that almost every Indian knew those culture-molding stories, so they were common fiction ground easily referenced in any conversation or story, as in my story “Matters of Balance,” which plays off the Mahabharata. Also, there’s Indian fiction in various indigenous languages: Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, Tamil, etc.

In Campion School we read some Hindi stories as well as English, though mostly the latter. I believe that early multilingual experience helped my writing ear. There again, most of America reads and writes in only one language, English. I think experimental fiction, where form takes priority over content, may be a genre as yet unexplored in Indian fiction. But it seems to be a dead or dying genre, now.

Bill: How do you see the role of literature in bridging gaps between different cultures?

Sohrab: It’s hard to tell the degree to which it does that, without a study through surveys, etc. Clearly, it has done so to some degree, and continues to do so, but I think the way it does that has been undergoing a change. Used to be that, wherever we were from, we’d come to know about, say, the Russian or French cultures through reading their respective stories, often in translation, about Russians interacting with other Russians in Russia or the French interacting with other French men and women in France. And they in turn would read stories about us interacting with our fellow Americans or Indians or Englishmen, as the case may be, and they’d learn about our cultures that way. So the literature wasn’t about characters bridging cultures, just about characters immersed in separate cultures. Whereas now, more and more, we have international or global or, as I like to call it, cross-national stories about, say, Jamaicans and Pakistanis interacting with Englishmen in England, as in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. And the multinational characters are themselves in the process of trying to bridge the cultural gaps between one another.

Take that a step further and we have such stories taking place in more than one national setting, even across the continents. I discussed this as visiting writer in residence at Augsburg College, Minneapolis, in a 2004 craft lecture on “Multiple Sense of Place in Contemporary Fiction,” as opposed to the traditional strong single sense of place exhibited by, say, William Faulkner. The more our lives play out globally in this age of globalization, the more our literature will reflect that global setting. So the subtitle of my collection is “Stories of India and America,” reflecting an alternation between the two countries all the way. The novel I’ve been working on, Go Home, which gets its name from a phrase yelled at foreigners in the aftermath of the Iran hostage crisis, features an Indian character of Persian origin in America searching for his place in the world.

It would be interesting to track the roots of this expansive international literature: colonial literature, such as E. M. Forster’s work, expat writing, such as Hemingway’s, and postcolonial lit, such as V. S. Naipaul’s and Jamaica Kincaid’s, all come to mind. Of course, war stories, inherently cross-national, go back all the way to the ancient epics: Greek, Persian, Indian, Irish, British. But they weren’t exactly bridging cultures …

Bill: How did you receive the “Most Beautiful Books” award?

Sohrab: When my book’s German translation, Fahrschein bis Minto, was released at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2006, it was selected to a list of fifty “Most Beautiful Books” of the year. As far as I know, that was quite literally meant as an award for the artwork and design of the German edition at Mitteldeutscher Press, not anything to do with the book’s content. Funny story, though: the cover design etc. at first had been quite different, more humorous than artistic, to go with a new title they’d envisioned: Minto Hostel. Apparently, that was meant to ride the wave of popularity of a movie called Hostel. But when I explained to my translator-editor Thomas Loschner at Mitteldeutscher that Ticket to Minto functioned as a metaphor for the reader’s passage to a destination straddling East and West, they went back to the original title and redesigned the cover.

Bill: What was it like reading at the Zoroastrian Association in Houston, Texas? What year was that?

Sohrab: It was a great event! The year was 2003. The ZAH had recently built and opened its lovely new cultural center, and the event was part of an inaugural series. I reunited with old friends, who put me up for the weekend. There was a nice buildup, with a reading at the River Oaks Bookstore the evening before and an interview on an Indian radio show, “Music Masala,” in the morning. As a result, the center’s reading room was packed. I read “Holy Cow,” a story about Parsi characters in Detroit, then fielded some great questions and signed a bunch of copies. All of that, and I got to see a great new city too.

Bill:You write about tennis players — do you still play? Have you won any tennis championships?

Sohrab: I had to stop playing tennis years ago and turn to table tennis, because of chronic tendonitis in my playing arm. Though I played inter-collegiate tennis briefly in India, it came second to inter-varsity badminton, where I captained my college team. The only tennis tournament I remember winning was the inter-hall tournament at IIT. My sporting accomplishments were modest, all at a college or city level. But I came from a sporting family, as I describe in a piece about my late father, “Flicker Fracis is Alive,” for FEZANA (Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America) Journal. As I wrote in there, “it enriched my life,” and “my stories would reflect [my father’s] love for sports, a love he passed on to me.” Though only peripheral to a few stories, sport was a rich field to mine for metaphors about the game of life.

10 Responses

Great interview, Bill. I’m

Great interview, Bill. I’m going to check this guy out.

We Americans tend to focus

We Americans tend to focus only on our own bellybuttons: to me, what’s important may be Southern; to you from NYC, anythng out of Manhattan, the Bronx, etc. is of little interest; to another from Los Angeles, the sun rises and sets on movies, castings, and scripts.

The world of literature and English is much more extensive. In India or China, you will find as many writers and speakers of English as you will find in the USA.

Americans may expect the world to know of our cultural icons (e.g., Billy the Kid, Babe Ruth, Davy Crockett, et al.), but we need to pay attention to similar names from other great cultures.

great interview…my only

great interview…my only gripe is i wish it was a little longer…now i have another author to add to my list when i’m browsing the book sections of goodwill

“I think experimental

“I think experimental fiction, where form takes priority over content, may be a genre as yet unexplored in Indian fiction.”

Wow, that’s a pretty sweeping statement. Coming from India (Tamil Nadu) I can say that quite a bit of experimental fiction is indeed being done in India’s vernacular languages. In fact there has been the argument of form over content going on in Tamil writing from the 80’s and 90’s.

The problem is that they are not being translated into English and are hence left with a limited readership.

Yes, Ajay, I was wondering

Yes, Ajay, I was wondering about that statement too. I don’t know specifically about Indian fiction, but it seems doubtful to me that experimental fiction doesn’t exist within any literate society in the world today.

I add my appreciation, Bill.

I add my appreciation, Bill.

Thanks for the comments,

Thanks for the comments, everyone. Sohrab knows I don’t agree with him on certain points. For example, I still think, and hope, experimental fiction is not a dying genre. Also, he is not as enthusiastic about self-publishing as I am. I think these things reflect his particular academic background, which I respect. He’s a very good writer and an excellent writing teacher. I’m looking forward to his novel.

I imagine if one has a

I imagine if one has a contract with a major publishing company that self publishing wouldn’t be very exciting.

In the past the self publishing route was called a vanity press and to some degree (maybe a large degree) that was an apt description. It costs a lot of money to print up a thousand books.

But with ePub and the kindle marketplace, self publishing is truly viable.

There’s always so much vitriol aimed at big corporations, but seldom are big publishing interests included. I like seeing an independent writer succeed at the Kindle store big time, as some have done.

TKG, you are a wise man. My

TKG, you are a wise man. My book is available on both Nook and Kindle.

You’d be hard pressed to find

You’d be hard pressed to find a better writer.