Writers create whole worlds; we see this most often in the realms of science fiction and fantasy. Eamon Loingsigh is a Brooklyn writer whose world is fully grounded in urban reality — the rough waterfront docks of Auld Irishtown in Brooklyn, 100 years ago. His first novel Light of the Diddicoy introduced a teenage striver, Liam Garrity, who arrives from Ireland and quickly comes to understand how high the stakes for survival are in New York City. The second book in this trilogy, Exile on Bridge Street, came out in October. The boundaries of Eamon Loingsigh’s own difficult literary exile can be mapped via the eclectic, inquisitive articles he has contributed to Literary Kicks over the past few years, including Revolt on Mount Parnassus: An Allegory in Copy/Paste, Lautreamont: The Other, The Salinger Mystique and Taylor Mead: A Bowery Glimpse.

Marc: When Light of the Diddicoy came out in 2014 you told us about your mission to represent the unknown history of Irish-Americans in Brooklyn, and in New York City. But your trilogy is not only about a chronicle of a people but also the story of one lonesome immigrant, struggling to survive in a frightening land. I think William Garrity is a great character, a teenager getting by (just barely) by the power of his courage and wit, and a tormented soul who is forced to make terrible choices without looking back. Is the hero of your book meant to symbolize the Irish-American experience, or does he symbolize something more personal to you?

Eamon: Liam Garrity is fourteen when he travels from a farm in Ireland to New York City, so obviously Liam represents innocence in the summation alone. When you introduce a reader to a new world, such as Brooklyn during the 1910s, it is helpful that the narrator was also experiencing it for the first time. Millions of Irish landed in New York City with no money, but gobs of hope and limitless will. Liam embodies these traits, but they are not just Irish traits, they are human, and the same can be said of our Italian, Jewish, Asian and German ancestors as well as today’s Latino or Arabic immigrants. Hoping for success in a new world so that he can his help his family, like so many immigrants have experienced in this city, is a sweeping, multi-generational theme.

Marc: In Diddicoy, Liam Garrity ricochets between several gangs of Irish dock workers, playing off his presumed loyalty to each for his own survival. In Exile on Bridge Street, questions of loyalty and suspicion continue to loom ominously. Is there a philosophy of life embedded in this tale of shifting alliances? Who is your hero ultimately loyal to, and who do you think he should be loyal to?

Eamon: Again, some themes are just so widespread that they can’t simply be embedded in a single timeframe. Loyalty is demanded of us to this very day. Maybe not to gangs, but what employer doesn’t demand your loyalty? In theory, many people see whistleblowers as heroes, but in the real world, they are blacklisted and their lives are turned upside down. In the novel, the threats of being called a “tout” (Irish slang for “informant, traitor”) are much more dire and in a place as dangerous as Irishtown was, a grizzly death may come upon you for such an allegation. In the story, he is loyal to Dinny Meehan, the White Hand Gang’s leader and the man atop the labor racket in Brooklyn. But Liam only wishes to help his family, and since Meehan can assist him the best, the boy is loyal to the leader. But with Meehan’s motivations being murky and his power constantly challenged from within and without, remaining loyal to Meehan may end up being the greatest danger.

Marc: “Tout” is a great slang word to know, and so is “diddicoy”, which signifies a particular kind of outsider status, a desperate long-running alienation. As a novelist, do you also feel like a diddicoy?

Eamon: I think almost all Americans are diddicoys, which is to say they have “mixed blood”. Rarely is anyone of “pure blood,” for that matter, but in the United States, we are known for having a varied genealogy, but often can break them down into percentages (1/4 Lakota Indian, 1/4 Irish and half Jewish). But to answer your question, yes I do feel like an outsider, but I think most people do.

Marc: But isn’t “diddicoy” a metaphorical condition for Liam, and for you? Maybe I’m off on my own tangent here, but I wasn’t reading the word in its literal Romani meaning of “mixed blood” but rather in the sense of a divided identity, a tormented soul. Liam is divided for a few reasons, but mostly because his loyalty is both to his family back in Ireland and his “gang” in Brooklyn. Now, all of these identities may be “pure blood”, as far as anybody knows, in terms of Irish ancestry, right? But that doesn’t help Liam much at all.

Eamon: Certainly Liam feels like a gypsy-outsider for many reasons. He does have a divided, tormented soul, but he also comes from the rural West of Ireland and has landed in the biggest city in the world. He had never seen electricity before reaching New York City, but the people that take him in are in-effect refusing such technology. Dinny Meehan, the leader of the gang known as The White Hand, embodies that refusal of the future the most. It is he, and others that follow him, that do not trust the authorities and want only to live within their own community, violently defending their neighborhood’s borders from outsiders. At the end of Diddicoy, it is established that Meehan is against time and change itself. And against modernity in general, which is symbolic for a group of first/second/third generation Irish living in a foreign land, yet grasping onto their Irish roots. Their forebears originally landed in New York to escape “Ireland’s greatest tragedy,” as the famous historian Tim Pat Coogan once described the Great Hunger of 1845-1852 which, even if you ask most Irish to this very day, was not a famine at all. Millions of dollars worth of food was being exported by the British colonial power in Ireland (from Irish proper) while millions of Irish children, women and men died on the roadsides or desperately left in “coffin ships,” often dying and dumped into the Atlantic Ocean. The survivors settled shoeless, horrifically disfigured by starvation and the most extreme poverty, in places like Irishtown in Brooklyn.

All of this history, the Code of Silence the gang lives by, the refusal to obey Anglo-American law, distrust of hospitals, calling those gang members who speak with outsiders touts makes Liam and all that follow Dinny Meehan’s lead feel like gypsies, i.e. diddicoys.

Marc: I know that you’ve met some of the descendants of Dinny Meehan, the hard-bitten gang leader to whom Liam pledges his loyalty. What was it like to interact with the relatives of the power figure at the center of your books? Did it surprise them to meet you? Did anything about meeting them surprise you?

Eamon: Yes, I did meet two grand-daughters and a grand nephew of Dinny Meehan. They are amazing people and have been very, very supportive of the books. I was concerned that because this is fiction, that they might be unhappy that I didn’t stick to facts only, but they’ve appreciated how the character has been handled and encouraging.

I get emails regularly from people who have relatives that were members in the gang and characters in the books. It’s amazing how many people also ask me to track down genealogical records of their ancestors. It really shows that there’s a lot of interest in the American past, particularly through family connections.

Marc: Speaking of divided identities, I’m fascinated by the fact that you in your “Auld Irishtown” trilogy create a world that is full of life and joy and pain but that mostly (at least as far as I’ve currently read) has little time for books or finer literary thoughts. I get the feeling that Liam would have a sensitive literary mind if he didn’t have to scramble to survive on the waterfront … but the literary life is not an option for him. But your first article for Litkicks (which I still remember being so excited to publish) was about the French poet L’autremont, who appeared to me a very “literary” kind of diddicoy, and who lived a life very different from that of a Brooklyn dockworker. How did you allow your own literary consciousness to inhabit the souls of these characters who mostly do not have time to read?

Eamon: Like Liam, I didn’t have a great education growing up. I self-taught (which often makes me feel like a diddicoy, as I didn’t have literature explained to me by a professor), and actually read all of the books I always heard were the most “literary.” I read thousands of books as fast as I could to catch up after having a near-death experience when I was eighteen, and then experiencing my mother’s death when I was twenty years-old. Liam has a similar dilemma. He is forced at the young age of fourteen to join a gang in order to make money to help his desperate family. Along the way, he finds out through clues (same as how I learned of literature) about Brooklyn’s most famous poet, Walt Whitman. He longs to know more about Whitman, and eventually is given a copy of Leaves of Grass, which he studies when he has the rare moment to do so, and applies the poems to his current life. He is fascinated with how the words make him feel and he escapes the terrible reality of his life by reading the poetry of a great man. After the series ends, it is assumed Liam continues his reading for years and years until when in his 90s, he decides once and for all to write the story about when his father sent him from the farm in County Clare, Ireland, to Brooklyn. And that’s where the story of Auld Irishtown begins, October of 1915 when he was only fourteen years-old and “crossing over” as the Irish say, from the old country to the new.

Marc: What do you think about the literary environment in New York today?

Eamon: When asked that, I immediately think of a famous line by poet Adrienne Rich: “Art means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table which holds it hostage.”

I also went to a reading by Luc Sante recently, who spoke about some of my favorite French writers. He was talking about how the most famous writers broke rules and flouted the literary elite of their day. Today in New York, there is a plethora of rule-following writers who pander to a system that will never allow their voice to be bigger than the system itself. It’s not entirely proven that these voices demand anything bigger anyhow. The system has its favorites, and those favorites were chosen because they play by the system’s rules. After the election this year, I hope that everyone sees that the system is self-satisfying and that rebels need to overthrow it. Just as Mr. Trump won a populist election by trashing the two major parties (and Mr. Sanders had success doing the same on the left), we need writers who can speak for the individual, not recite stale poetry at the same dinner table that holds them hostage.

Marc:I know you are striving, perhaps with the bitter intensity of an impoverished dockworker, to make the case to potential readers that the story of the Irish immigrant experience in old waterfront Brooklyn is a story that can have meaning and relevance to their lives. How has this been working out? What kinds of reactions have you had from readers and reviewers?

Eamon: Most readers pick up the book because they are interested in the history of the Irish in New York. What they find is a story filled with symbolism, references to events they hadn’t heard of (such as the explosions on Black Tom’s Island in 1916), a coming of age story and, maybe most importantly, that the gangs in New York were not put together because they enjoyed crime or were simple nihilists, but, as was in real life back then, gangs were a form of social support in an environment hostile to them. Men got together in groups (normally along ethnic lines) and dominated labor violently so that they could feed their families. There are constant references in the books to “need and necessity.” Therefore, when someone is killed it’s not the type of killing you’d see in Hollywood movie or cheap fictional biography of the lovable/violent gangster who comically has to “move the body” and there isn’t all kinds of Tarantino-style thug dialogue with quirky personalities. In this trilogy you’ll find the struggle of becoming American. An important part of becoming American is the inner struggle of assimilation, which for so many millions was torturous, having to turn their back on the culture of their homeland. Every character in the Auld Irishtown trilogy struggles with whether they are of Irish stock or simply another immigrant that accepts the Anglo-American way of life.

Marc: Why did you decide to make your Auld Irishtown story a trilogy? And do you think this has helped or hurt the public acceptance of your work so far?

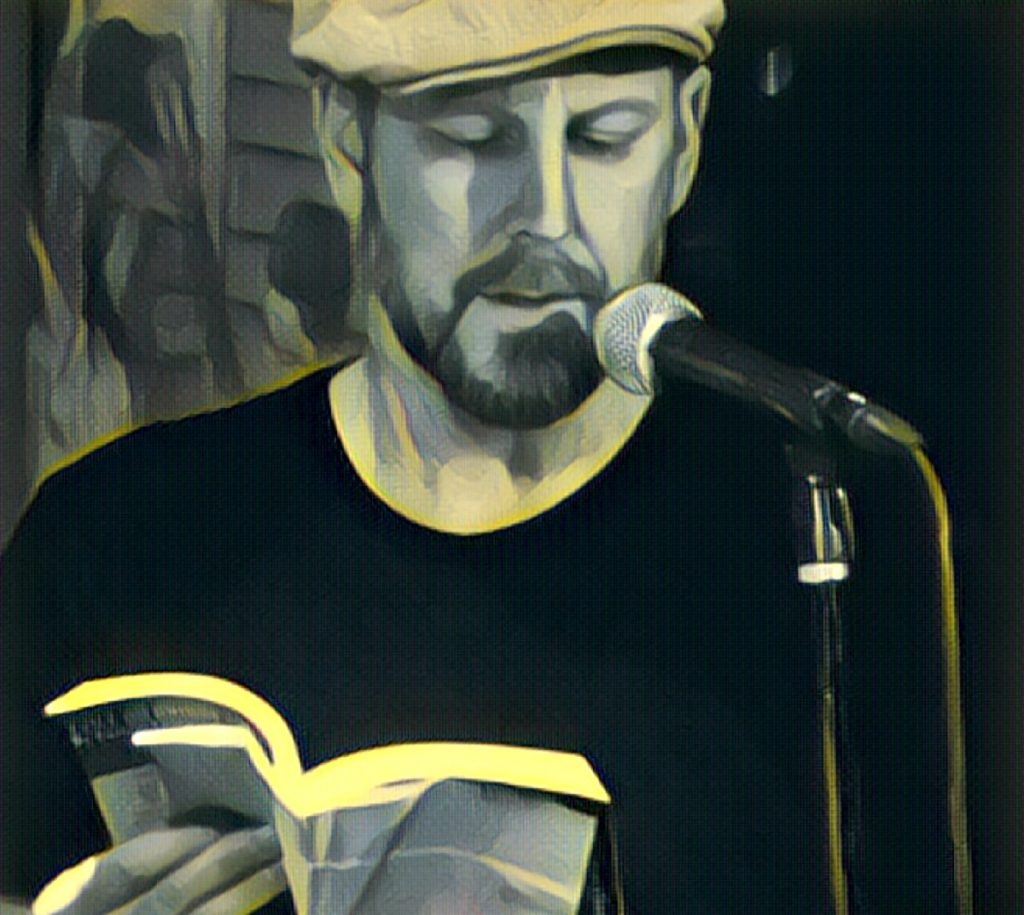

Eamon: At a recent reading at The Mysterious Bookshop, T. J. English (The Westies, Paddy Whacked) introduced me and spoke about the struggle this trilogy faces because it tells a truer story of a coming-of-age from the level of the street. A street-level story doesn’t always grab people’s attention because readers are very used to the omniscient storyteller. Here, the story is being told by a man in his 90s looking back to when his Irish rebel father sent him to New York months before the Easter Rising. He is looking back with a deep sadness for the terrible things he had done, but also to tell the real story America, that demanded the blood, and quite often the death, of all the immigrants and the exiled.

In the short-term, I think being a trilogy hurts the public acceptance. Readers often don’t want big picture stories, they want them easily defined and categorized. In the long-term, however, as T. J. English has described, the trilogy will be appreciated for its breadth in posterity. But as Louis-Ferdinand Céline pointed out in his famous work Journey to the End of the Night, “invoking posterity is like making speeches to worms.”

2 Responses

Great, insightful interview

Great, insightful interview by a very interesting author about his fascinating trilogy. The struggle of the Irish in Brooklyn described in EXILE ON BRIDGE STREET is reminiscent of the struggles of today’s immigrant populations.

Dawn Ades wrote, “The soft

~paste~

Dawn Ades wrote, “The soft watches are an unconscious symbol of the relativity of space and time, a Surrealist meditation on the collapse of our notions of a fixed cosmic order”.[3]

This interpretation suggests that Dalí was incorporating an understanding of the world introduced by Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Asked by Ilya Prigogine whether this was in fact the case,

Dalí replied that the soft watches were not inspired by the theory of relativity, but by the surrealist perception of a Camembert melting in the sun.[4]

– – – – – –

Great to see this interview, Marc and Eamon.

I am one diddicoy who looks forward to reading your book.